The Anglo-Zanzibar War was a military conflict fought between the United Kingdom and the Sultanate of Zanzibar on 27 August 1896. The conflict lasted between 38 and 45 minutes, making it the shortest recorded war in history. Interestingly, the recent Gen Z protest in Nepal was also remarkably short-lived—it began on September 8 and ended within 27 hours. The protests forced the government of KP Oli to step down, after which President Ram Chandra Paudel appointed Sushila Karki as the interim Prime Minister of Nepal. The goals of the Gen Z movement were to end corruption, reduce unemployment, promote good governance, and ensure economic equality.

On the recommendation of the newly appointed interim prime minister, the President dissolved the House of Representatives (HoR) and announced a fresh election for March 5, 2026. During the protests, at least 74 people were killed, and multiple government buildings, political parties’ offices as well as the parliament and the president’s residence along with private and commercial properties were set on fire, causing losses in trillions of rupees. This represents the greatest destruction of property in Nepal’s history.

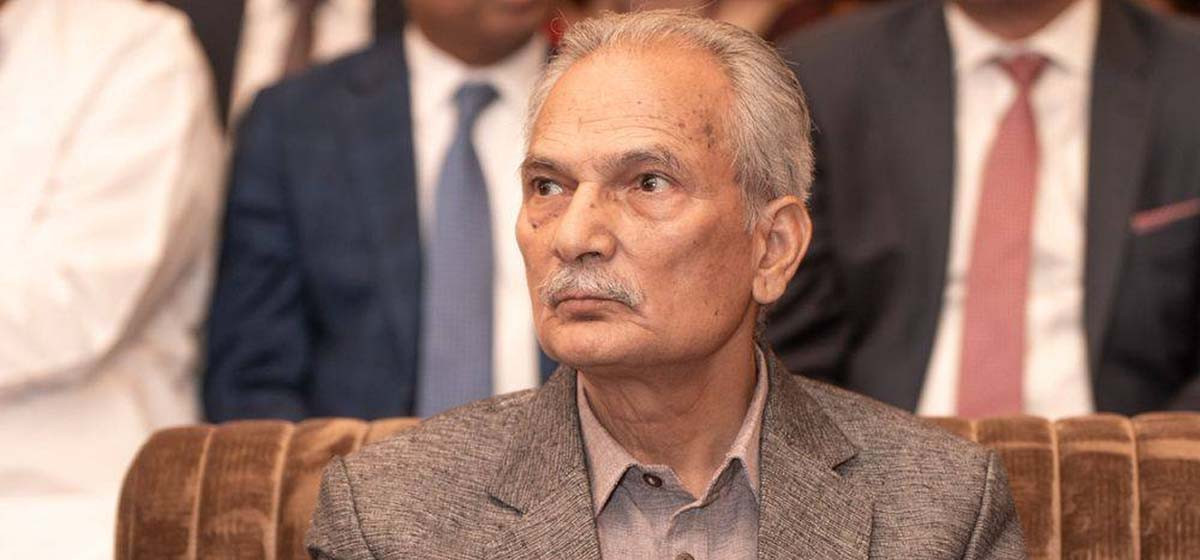

Given Nepal’s fragile economic health, the destruction of government and private properties poses immense challenges for the new government. Under these circumstances, Prime Minister Sushila Karki appointed Rameshore Khanal, former Finance Secretary, as the Finance Minister. He faces the formidable task of managing government resources during a time of massive destruction. Rebuilding these devastated infrastructures will take decades, not merely a year or two. Meanwhile, the government must also allocate funds for the upcoming HoR election on March 5, 2026 and provide support to the business community, which has suffered extensive property damage.

Currently, Nepal’s economy faces multiple challenges. There is a significant outflow of Nepalese workers to the Gulf countries in search of employment. Key productive sectors, including manufacturing and agriculture, along with real estate, construction, forestry, communication, and services, are stagnating. The economy largely survives thanks to external factors, particularly remittances sent by Nepalese working abroad. These remittances are primarily used to import goods to meet domestic demand. The service sector, which provides the largest share of jobs in Nepal, is heavily reliant on this cycle of remittance-driven imports. This dependency poses a significant risk to the economy. Additionally, although bank deposits are abundant, businesspersons are reluctant to borrow or invest due to an unfavorable business environment. Public debt has also increased alarmingly.

Beauties, build the thick skin

National pride projects and large infrastructure initiatives are further straining government resources. Projects such as irrigation systems, roads, drinking water facilities, and international airports with limited returns face long delays, escalating costs, creating pressures on both the revenue and expenditure sides of the state.

Nepal is also affected by broader economic and financial shocks. Poverty and underdevelopment are closely tied to the ongoing economic slowdown. Global trade disruptions, increasing trade restrictions, and protectionist policies by developed countries—especially Nepal’s neighbors—widen the trade deficit. More than half of Nepal’s remittances come from the Gulf countries, and rising conflicts in the Middle East could reduce employment opportunities for Nepalese workers, delivering further shocks to the national economy.

Economic policies in Nepal often fail due to complex systems, inadequate data, implementation challenges, conflicting interests, and the inherent difficulty of predicting future conditions. This leads to poorly designed, targeted, or executed policies.

The new finance minister is expected to put the economy on a sound footing, despite having only six months in office. Policy measures may include improving fiscal discipline, strengthening the financial sector through interest rate adjustments, reforming tax policies, diversifying production and exports, enhancing the business climate, providing financial aid to affected industries, and focusing on areas of comparative advantage.

Government revenue currently supports only recurrent expenditure, so Nepal requires financial assistance from domestic and external donors during this crucial period. Donor agencies and international communities—including neighboring countries India and China—are expected to respond positively by supporting reconstruction and economic development. Domestic investors and multinational companies may also consider increasing investment in Nepal.

A fair tax system and equal policy support are essential. Taxation must be equitable across income levels, corporate and individual taxpayers, urban and rural areas, formal and informal sectors, labor and investment income, and across generations.

Nepal can no longer attribute underdevelopment solely to political instability, mismanagement, or lack of resources. The country must embrace modern economic theories to industrialize, build capital-intensive manufacturing industries, develop modern financial systems, and create institutions that can compete regionally and internationally.

The new finance minister brings valuable expertise, having participated in several study groups including the High-Level Economic Reform Commission of 2082. His leadership could inject momentum and direction into Nepal’s ailing economy. Just as the reforms of the 1990s opened a window for foreign investment, the post-Gen Z protest presents a new opportunity for economic reform, laying the groundwork for more liberal and prudent policies.

_20200621105320.jpg)