Internal feuds have lately gripped all major political parties in Nepal, exposing how fragile their internal systems have become. These conflicts are an indication that parties have lacked healthy debate and transparent leadership that promotes collaborative and collective decisions and actions. Collaboration, open dialogue and concrete action on the issue pertaining to organizational structure and sharing of positions within parties and governments are largely absent, which gives rise to rivalry among leaders and their supporters.

Take the Nepali Congress. Despite having a democratic history, the NC is now battling infighting due to deepening factionalism. President Sher Bahadur Deuba is facing growing pressure from Shekhar Koirala and younger voices like Gagan Thapa and Bishwa Prakash Sharma. They want change, not only in how the party functions but also in how it leads in Parliament. The two factions, one loyal to Deuba, the other backing Shekhar, are heading for a face-off in the upcoming central working committee election. Talks are doing rounds that Shekhar's team might try to unseat Deuba as legislative leader. Though it's a tough climb, Shekhar is determined to try to topple the party chair. On the other side, some reports suggest the party president might step aside and put forward one of his loyalists to retain influence without holding the top post.

Meanwhile, frustrations are spilling into the provinces. In Bagmati, for example, Indra Baniya recently replaced Bahadur Singh Lama as the party's parliamentary leader, and that swap says a lot. Rather than settling issues through honest talks, the party leaned on elections as a shortcut. This policy of inclusion for some and exclusion for others has exacerbated the divisions within the party. Many now believe that unless the party returns to real internal democracy and moves ahead with a consensus and collaborative approach, the rift will only widen when the party goes to the 2027 election. Against this backdrop, winning a majority will be an uphill task for the country’s oldest democratic party.

19th Sawa Lakh Rot Festival begins in Gorkha

The ruling CPN-UML is not faring better either. Chairman KP Sharma Oli remains firmly in control, but that grip has come at the cost of distancing many of his party colleagues. Speaking out against him in the party has its consequences, and that has created a climate where most stay silent. Discontent has simmered below the surface. Former President Bidya Devi Bhandari's return stirred the waters. Her backing of sidelined leaders like Karna Bahadur Thapa and Ishwar Pokharel briefly took many Oli loyalists by surprise. But Oli quickly responded by stopping them from exerting influence. He not only suspended Bhandari's party membership but also scrapped age and term limits, sending a clear message that he is more focused on holding onto power than building a collaborative, more open party.

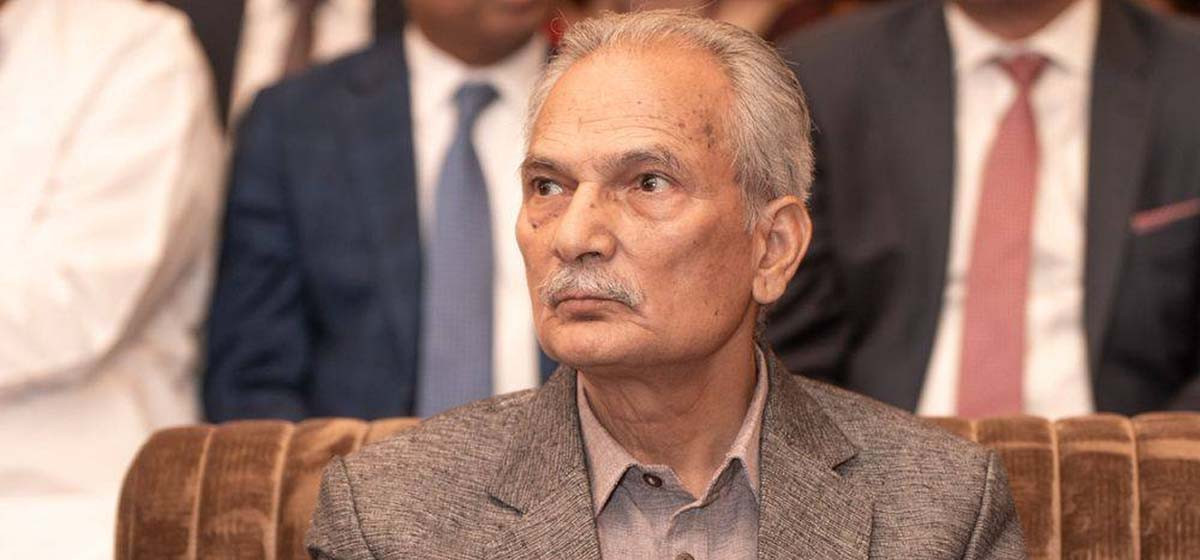

The CPN (Unified Socialist), headed by Madhav Kumar Nepal, too, has found itself in rough weather. Leaders like Madhva Kumar Nepal, JhalanathKhanal and Bam Dev Gautam, who left the UML after feeling squeezed out. But even in the new party, old habits of sidelining competitors or leaders with rival voices remain. Madhav Nepal, who had promised more open leadership, now faces growing backlash.

In what appears to be new cracks in the party, Khanal accused Chair Nepal of authoritarian behavior after Nepal made a remark suggesting Khanal should quit if he disagreed with the party leadership. Khanal didn't hold back but called Nepal's words indecent and said disagreements like this should be settled in the party, not in public. Another blow came when Ram Kumari Jhakri openly criticized Nepal, especially after his name was linked to the Patanjali land scam. Complaints about how appointments are made and power is distributed are piling up. The party that was supposed to stand against Oli's style now seems to be repeating the same mistakes.

The story of the Maoist Center is not different. Led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda), the party once inspired many through revolution, but nowadays its leaders feel the party has lost its direction. Longstanding senior members like Janardan Sharma have started challenging Dahal's leadership. Janardan has repeatedly made public remarks about internal conflicts within the party, spurring Dahal to warn him of dire consequences if he continued speaking about internal matters. For the past few occasions, Dahal and Sharma have been engaging in public exchanges of accusations, leading, as many termed it, the party into a two-line ideological struggle. Earlier, leaders like Mohan Baidhya, Biplav, and CP Gajurel had walked away, citing differences with Prachanda. Many say Dahal's refusal to welcome opposing views is holding the party back, as it has grown weak in national politics.

The Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) is also facing the same quandary. Chairman Rajendra Lingden's decision to relieve veteran leaders like Sagun Sunder Lawati, Dhawal Shumsher Rana, Nawa Raj Subedi, and Prakash Chandra Lohani of their responsibilities has widened the rift. Some of them have even taken their complaints to the Election Commission. That's not something you expect from a party where founding members have been brushed aside. It shows how badly internal cohesion has broken down.

Smaller outfits like the Nagarik Unmukti Party haven't escaped the chaos either. Ranjita Shrestha was recently pushed out of leadership following allegations of running the party affairs at her will and after she was tied to the Pokhara land scam. Her father-in-law took over, and her husband, Resham Chaudhary, backed the decision. The party, once a fresh alternative, now looks split and uncertain.

Across all these parties, top leadership has exhibited a restrictive tendency. Almost all of them are inclined to reward loyalty and punish dissenting voices. Rules and regulations are changed or tampered with to suit those who hold power, and the top leadership take decisions in backrooms rather than in party meetings. As open dialogues are restricted, factional divides take root. Top party leaders should welcome disagreement, encourage open discussion, and listen to voices beyond their inner circles. That's the only way to rebuild trust among all party leaders, workers and members, which will help them boost their image in the eyes of voters.