A couple of years ago, I visited one of the most faraway villages to meet the Jesuits working there. While I was there, I was told that an elderly woman was seriously ill. I accompanied one of the Jesuits as he went to visit her, and along the way, a few concerned villagers joined us. When we arrived, it was clear her condition was critical, so we took her to the health post. The medical staff informed us that she was suffering from acute asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

What shocked me even more was learning that she lived alone. As a single mother, with all three of her children working abroad, she had no one to care for her and was surviving solely through the kindness of her neighbors.

On our way back from the health post, the Jesuit who had brought me was sharing updates about recent events in the village, but my mind remained with the woman. Her face, her struggle, and her loneliness haunted me. I recalled a message from Pope Francis to the participants of the 47th Social Week for Italian Catholics, held in Turin from September 12–15, 2013. He wrote, “A population that does not take care of the elderly and of children and the young has no future, because it abuses both its memory and its promise.” His words resonated deeply in that moment.

These words speak powerfully to Nepal’s present-day reality. We are facing a growing yet quiet crisis, one that affects the very heart of our homes and the future of our nation. The elderly and children, once deeply cherished within our families and communities, are increasingly being neglected. This shift represents not only a breakdown in intergenerational care but a deeper erosion of the values that have long shaped our society.

Nepal has long taken pride in its rich culture of honoring and respecting elders. Matatirtha Aunsi (Mother’s Day) and Kushe Aunsi (Father’s Day) are two of the most cherished occasions that hold deep emotional and spiritual significance. Married daughters eagerly await these special days, returning to their parental homes with an array of sweets and thoughtful gifts to celebrate with their mothers and fathers. Similarly, sons living away make it a point not to miss these occasions, coming home bearing gifts and affection.

Worth of stories

Within the traditional Nepali joint family system, grandparents were not only ever-present but deeply woven into the rhythms of daily life. Far from being sidelined, they were the living heart of the household, caretakers of children, transmitters of wisdom, and custodians of culture and faith. In the soft light of early morning, a typical village courtyard would come alive with quiet activity. A grandfather might be seen seated on a pira (low stool), his grandchild nestled in his lap, gently lulled to sleep as he recited morning prayers or softly sang bhajans. Nearby, the grandmother would be preparing breakfast, her hands grinding spices on a silauto with lohoro (stone slab) or stirring a pot of lentils over a chulo (traditional clay stove). As she worked, she would narrate ancient dantekatha (folk tales), filled with moral lessons, heroes, gods, and ancestors, passing down values more powerful than any classroom could offer.

In these households, the elders were the first to rise and the last to rest. Their day began with offering incense at the family shrine and ended with gathering the younger members for evening prayers. When tensions arose, be it a quarrel between siblings or a disagreement among adults, it was often the calm voice of the grandparents that brought resolution. Their authority was not enforced by command but earned through years of lived experience and quiet service.

During festivals like Dashain, Tihar, the role of elders became even more pronounced. It was the grandparents who prepared the sacred spaces, guided the rituals, and applied tika with trembling but reverent hands, invoking blessings upon every member of the household. These were not just rituals, but they were sacred acts of continuity, binding generations together through shared faith and love.

The joint family structure allowed for constant intergenerational interaction. Children did not grow up isolated within nuclear units; rather, they absorbed values by observing. They watched how elders treated guests, how they responded to misfortune with patience, how they offered a small portion of food to their pitri (ancestral spirits) before meals, and how they gave to others even in times of scarcity. This daily witness shaped the character of the young far more deeply than mere instruction.

The presence of elders also brought emotional and spiritual grounding. In times of illness, grief, or uncertainty, their wisdom provided a steadying hand. They reminded the family of what had been endured in the past, and what could be overcome in the future. Their stories were not just entertainment; they were testimonies of resilience and hope.

In recent years, the strong family bonds that once held our society together are starting to loosen. Like an old dhaka cloth slowly unraveling, the threads of our joint family system are coming apart. With more people leaving their homes, some to the cities, others to foreign countries for work, and with rising costs of living, the way we live together is changing.

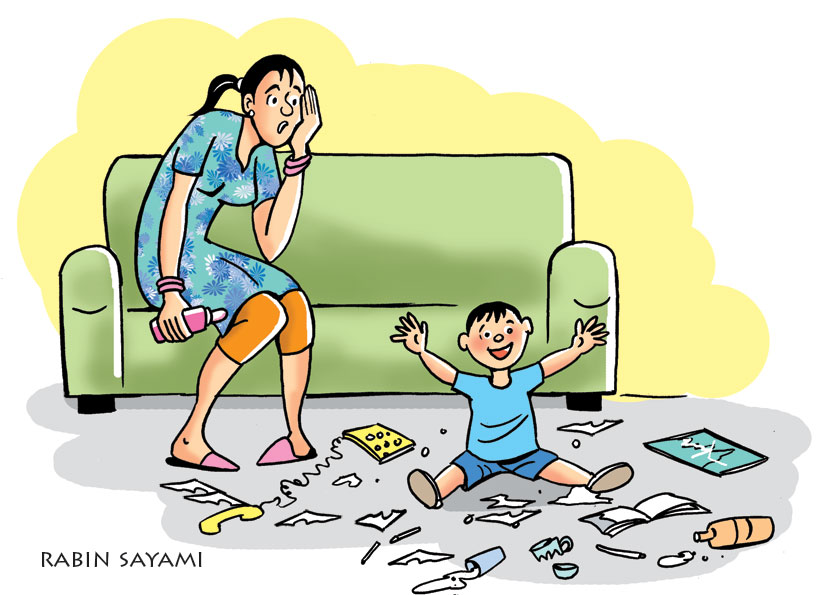

The big, warm homes where three generations once lived under one roof are now turning into small, quiet houses with just parents and children. In this shift, many elderly parents are being left behind in the villages, sitting alone on their verandas, waiting for visits that rarely come. Others are placed in old age homes, not because they are weak, but because they are seen as an extra burden in today’s busy life. Their voices fade into silence. Their wisdom, like old songs, is forgotten. Their stories, like yellowed photographs, gather dust. These elders are the living memory of our culture, but we are pushing them to the side. And with them, we risk losing the very roots that keep our heritage alive.

Our children, the bright future of our nation, are facing a quieter, but equally painful kind of abandonment. While Nepal has taken important steps in education and legal protection, the shadows of exploitation still linger.

Every day, thousands of children work long hours in brick kilns, dusty farms, roadside eateries, and even inside homes. According to a 2021 joint survey by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the International Labour Organization (ILO), and UNICEF, an estimated 34,593 children aged between 5 and 17 reside in brick kilns. Of these, around 17,738 (approximately 10% of total workers) are engaged in labor, with 96% identified as being in child labor.(Report on Employment Relationships in the Brick Industry in Nepal’, UNICEF, January 2021). Some children vanish across open borders, victims of trafficking, while others suffer silently from emotional and sexual abuse, often through the dark corners of unregulated online spaces.

The neglect of the elderly and the exploitation of children are not isolated issues; they reflect a deeper crisis of values. When we disregard the elderly, we sever ties with our heritage. When we fail to protect our children, we compromise our future. In doing both, we undermine the moral foundation of our nation. This is not merely a domestic or personal issue; it is a national concern that demands collective response.

Nepal stands at a turning point. We can either let the threads of our society slowly unravel, or we can choose to weave them back together with care, love, and respect for all generations. A better future will be built when every hand and heart plays a part. Religious groups and community leaders can help by creating spaces where seniors share life stories, and youth bring fresh energy. A temple courtyard or a phalchha where a grandfather teaches folk songs to children, or a village hall where young people help elders with daily tasks. These are the moments that keep our society strong.

Families, our first home should bring back the warmth of togetherness. Through small acts like a grandmother telling bedtime stories under a warm quilt, a father showing his son how to plant a tree, or a mother cooking with her daughter while talking about life, values like love, respect, patience, and care are passed on.

Communities and schools must become places where the past and future walk side by side.Imagine classrooms where students learn both science and folk tales. Think of a school project where children interview their elders, learning history through the eyes of those who lived it. A community where festivals are celebrated together not just with music and food, but with meaning. This is how we build a Nepal where every child is lifted up, every elder is held with honor, and every home becomes a place of learning, laughter, and love.