KATHMANDU, July 30: Various reactions have emerged immediately after the release of the Film Bill 2081 BS, which the government says is aimed at regulating, promoting and managing the film sector.

The government introduced the new bill after concluding that the old Film Act, issued in 2026 BS, doesn’t align anymore with the current digital era and technology-based communication system.

While some see the Bill as a necessary reform, others view it as a tool to control freedom of expression. Independent filmmakers, directors, writers and artists have called the Bill “centralized and regressive.” It is claimed that the bill covers modern aspects such as digital media, foreign film screenings, censorship, registration of producers/directors, and online streaming.

Some of the key provisions of the bill include mandatory registration of producers, directors, or film companies. It also states that all audio-visual content, whether shown in theatres or on online platforms, must receive approval from the censor board.

The Bill mentions that content from online platforms like YouTube, Netflix and MX Player—classified as OTT platforms—can also be subjected to censorship.

Several artists, criticizing the Bill as regressive despite its aim to revise and unify film-related laws, have called for amendments.

Actor Dayahang Rai, directors Nabin Subba, Manoj Pandit, Nischal Basnet, Khagendra Lamichhane, Anup Baral, and others met Minister for Communication and Information Technology (MoCIT) Prithvi Subba Gurung to present their concerns along with proposed amendments.

Five ways to boost creativity

They have also met with leaders of various political parties to point out flaws in the bill. “We met the minister to request some necessary amendments to the Bill being introduced by the government,” said actor Khagendra Lamichhane. “We hope our concerns will be addressed.”

Stating that film-related laws should foster the development of cinema, he argued that strict censorship regulations would only restrict the industry. “If there are any shortcomings, they should be addressed,” he added, “but it’s unfair to judge the entire sector based on fear of isolated incidents.”

He said that artists are also part of this country and can act responsibly.

The artists emphasized recognizing film as a cultural asset and making the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation the key institution with a clearly defined role.

They also suggested ensuring leadership from film professionals in the certification board and adopting a model of self-regulation for digital content instead of direct censorship.

They proposed establishing provincial-level boards and coordination systems in line with the spirit of federalism, and highlighted the need for a clear legal foundation for film archives, research, institutions, and grant systems.

Actress Dipa Shree Niraula argued that films cannot be bound solely by laws. “It’s normal for new bills to be introduced over time,” she said. “But the bill should not be mandatory or controlling. It should aim for the overall development and prosperity of the film sector.”

The government side claims the Bill also has positive aspects. Nepal’s film industry has long operated informally. The Bill aims to institutionalize the business by mandating the registration of producers, directors, and companies, Spokesperson for the MoCIT, Gajendra Kumar Thakur claimed.

The government believes the Bill will play a key role in protecting and promoting Nepali films. “We are seeking regulation, not control,” spokesperson Thakur said, “So there’s no need for panic.”

Due to the overwhelming influence of foreign films, Nepali films have started disappearing from theaters. The Bill aims to protect local content by prioritizing Nepali films and limiting the number of foreign films, which the government sees as a positive step, he said.

The government argues that since violent, obscene and hate-spreading content is increasingly appearing on YouTube and OTT platforms, the Bill seeks to create a decent digital environment by controlling such content. “Anything prohibited by the constitution cannot be allowed anywhere in the world,” said Thakur. “Beyond that, the government is flexible.”

The Bill also aims to organize the film classification system and promote child-friendly content—a significant but under-practiced area in Nepal.

Despite this, some filmmakers say the Bill still has controversial provisions that need to be revised. They believe certain dangerous and controversial clauses could seriously affect freedom of expression, creative freedom, and individual rights.

These include the widespread provision of censorship, unnecessary control over OTT platforms, the threat of fines and imprisonment, and the exclusion of stakeholders in drafting the Bill.

“Great works cannot emerge in an atmosphere of fear,” added Khagendra. “Filmmakers themselves need to act responsibly.”

Spokesperson Thakur noted that not everything is finalized yet. “The Bill now belongs to parliament,” he said. “If discussions and debates reveal the need to remove certain provisions, that can still happen.”

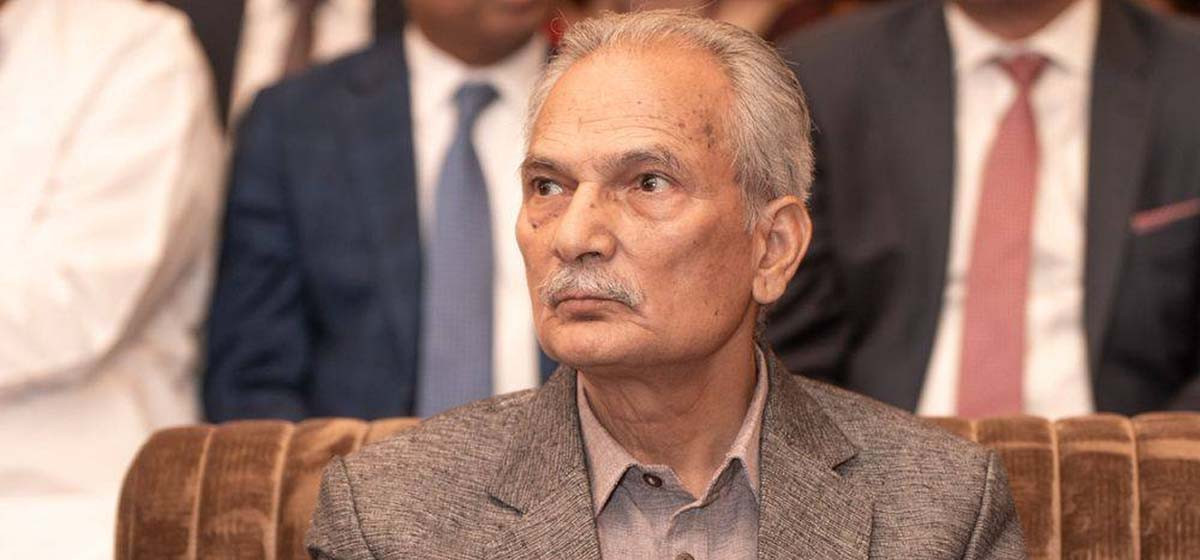

Dinesh Raj Dahal, aka Dinesh DC, Chairperson of the Film Development Board, said bringing a new version of the Film Act, which hasn’t been amended since 2026 BS, is a positive initiative.

He clarified that there’s no need to panic, acknowledging the Bill needs improvement and stating that necessary suggestions have already been forwarded to the concerned authorities. “The process of removing unnecessary provisions has already begun,” he said. “As a filmmaker, I am especially attentive to issues around censorship.”