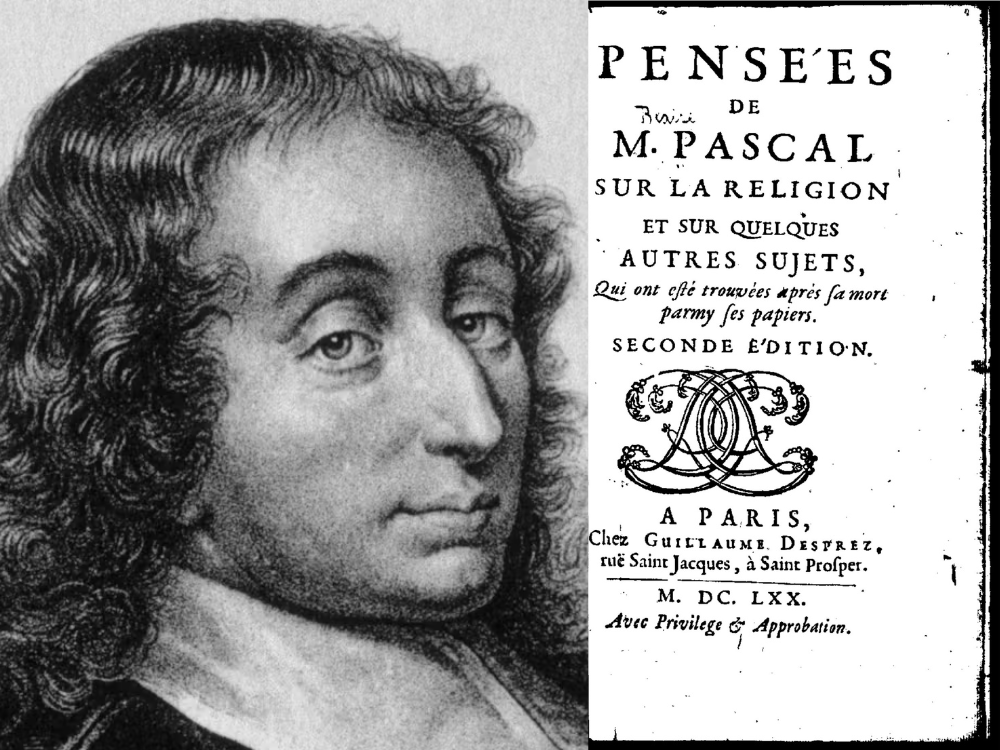

In his posthumously published book Pensées (Thoughts) which comprised previously unpublished notes, 17th century French polymath Blaise Pascal introduced the claim that people have to wager on whether or not to believe in the existence of God. One of the most recognized philosophical argument supporting the belief in existence of God, Pascal’s Wager, draws a 2X2 outcome matrix of choice between believing or not whether God exists against the reality of existence of God to suggest that a rational agent would rather inhibit the belief in the existence of God to avoid the terrible outcome associated with not believing in God when God truly exists.

Widely considered to be the father of probability for his contribution to the formulation of probability theory along with mathematician Pierre de Fermat, Pascal employed an earlier form of a probability distribution table and decision theory to analyze the outcomes for four different cases involving the belief in God against the reality of her existence. He attributed the outcome of believing in God while she exists as having infinite gain, thereby super-dominating the other outcomes where such infinite gain of believing in God is not existent (Pensées, note 233).

It is important to note that Pascal is not arguing that God exists but simply that we have a reason to believe in the existence of God. But the wager raises the question of what would happen if Pascal’s formulation of God is wrong and there is no infinite joy in the right outcome (believing in God when she truly exists). Therefore, when he raises this argument, there seems to be an implicit bias regarding the conception of God, that could be better understood if superimpose another conception of God in the wager.

Who is God?

Towards the end of the third meditation of first philosophy, Descartes mentions that a property of God is that she does not intervene or participate in the life and decision-making of her creations. He states that his idea of God is that of a natural unit that doesn’t invite or even permit interference (Descartes, 80). In the note 77 from Pensées, Pascal criticizes this attribution of God by stating that:

“I cannot forgive Descartes. In his whole philosophy he would like to dispense with God, but he could not help allowing Him a flick of the fingers to set the world in motion, after which he had no more use for God.” (Pensées, Note 77)

One possible reason why Pascal argues against such a non-intervening property of God is that his wager would not sustain if we were to abide by the cartesian picture of God. The infinite cardinality associated with believing in God when she truly exists would not exist if we think of God as someone who does not intervene. In addition, the negative cardinality in the form of terrible punishment associated with not believing in the existence of God when she does exist, also disappears in absence of the intervening power of God.

It seems like the outcomes of the wager would not be impacted by the possibility of the existence of God, i.e. the outcomes would be the same regardless of the truth of existence of God. And if the outcomes in the 2X2 matrix are not dependent on the truth of existence of God, the entire wager becomes invalid as people would be forcing themselves into believe in the existence of God where there is no merit in inhibiting such a belief. However, not all arguments advanced by Descartes would be readily rejected by Pascal as some Cartesian claims coincide with Pascal’s arguments. It seems likely that Descartes’ view on the cause of error could be used to support the wager. In the sixth meditation, Descartes claims that there is no error in nature, rather the language of error involved is extrinsic (Meditations, 100). According to him, true errors in nature only take place in the presence of mind. This propels him to argue for the existence of a passive faculty of perception that simply exists in us.

When we attribute the root of error to ourselves, Descartes seems to evoke a sense of possibility of error in not believing in the existence of god is rooted in our mind. But this Cartesian argument could also be employed against the wager. The foundational argument for the wager presupposes the good after death if one believes in the existence of God and she truly exists. This indicates that one could use the Cartesian view of error to claim that this very attribution of God to good could be a flawed result of a passive faculty of perception that creates the error. The argument that uses the Cartesian view of error to reject the wager rather than accept it seems to be more helpful here as one could always argue in the case of accepting the wager that the same sense of possibility of error in not believing in the existence of god rooted in our mind could also be used to question the possibility of error in believing in the existence of God.

Even when the cartesian view of God or any other view of God is not superimposed on the wager and we accept the outcomes according to Pascal’s conception of God, it seems like the cardinality (associated value) of each of the four outcomes could still be contested. As he is most concerned with the two outcomes in case of truth in the existence of God, Pascal does not highlight the negative cardinality of believing in God when she does not exist in the wager. He simply mentions that “you lose nothing”(233) when you believe in the existence of God when she doesn’t truly exist. This suggests that he presupposes that believing in the existence of God is a positive action. But it seems that such a decision would impact the lives of people, rendering their beliefs as mere lies. One might be afraid of an eternal damnation after life but what if there is no eternal damnation and you waste away your years simply in fear of such non-existent outcome.

Not all ideas of God suggest that there is an eternal damnation for non-believers. For example, Jehovah’s witnesses believe that the soul ceases to exist when an individual dies. Judaism shortens the “eternal” damnation to mere 12 months of punishment. This suggests that Pascal imbued his wager with an implicit bias favoring the existence of a particular sect of God, i.e. the Christian conception of God. This indicates that Pascal’s wager for believing in the existence of God already presupposes the existence of God, precisely, a Christian God. It seems like the wager might not sustain if such a presupposition is uprooted. In the absence of the presupposition of the existence of a Christian god, the cardinality of the outcomes of both believing and not believing in God when she truly exists is the same. In conclusion, Pascal’s wager, if not defeated by itself, is defeated by Descartes’ argument, and even when Descartes’ view of God is not superimposed on Pascal, other views of god could question the validity of the wager.